Introduction

DUECA currently provides facilities to create experiment interfaces (for operating your simulation or experiment), with gtk2, gtk3, and gtk4. The gtk2 interfacing is really obsolete, and it is currently difficult to find programs (old versions of the "glade" program specifically), to design these interfaces. So DO NOT USE THIS ANY MORE!

The gtk3 interfacing library is still well supported, and you can use the "glade" program to create your interfaces in a graphical manner, and when completed, these files can be used directly by DUECA to create interface windows. However, gtk3 is quickly being phased out, and to keep compatibility with the future, it is better to use gtk4.

The fourth version of the gtk toolkit, gtk4, looks a lot like later versions gtk3, but there are a number of important changes:

- In gtk4, almost everything is a normal widget, except for the menu system. Gtk3 still had different types of widgets for the toolbar (ToolButton, RadioToolButton, etc.). Gtk4 removed all of this stuff, and if you want a toolbar, just use a normal box, with normal widgets, and give the box a "toolbar" style.

- The same thing happened for "list" views and "tree" views. In gtk3, you can use a

GtkTreeViewto show data in a list with tree expansion. To provide data for this view, the data has to be copied to a "tree model", which could hold typical types of data (strings, numbers), in a table format. In gtk4 all that is gone. You no longer need to copy your data into a gtk-compatible table, instead you need to create a "factory", that in its turn creates widgets (normal widgets) to be shown in the table, and can link the data in those widgets to the data in your program. It looks a bit complicated (and examples are still scarce), so I added a section to this documentation that lays this process out step-by-step. - Another big change is the menu system. In gtk4 you can easily define a menu by its layout. However it won't do anything until you connected your menu items to "activities". The way in which you connect these items determines whether your menu items are shown as normal selections, have checkboxes to be toggled, indicating the state of the menu, or function like radio buttons in that you can select and activate one option from a number of possible choices. Another section lays out step-by-step instructions for that as well.

- The old and trusty "glade" program is not updated to gtk4, and its alternatives are either not complete yet ("Cambalache"), or work in a slightly different way ("Workbench"). I will outline the use of Workbench for building user interfaces.

Workbench

You can install workbench by Sonny Piers using flatpack:

flatpak install flathub re.sonny.Workbench

Run it using

flatpak run re.sonny.Workbench

Workbench lets you create an interface specification with a simple script editor. While creating the specification, Workbench can show you the resulting interface.

Ctrl-N will give you a new project, Ctrl-O gives a window to open an existing project. Each project is in its own folder, so you need a folder for each graphical interface you want to create. There are a number of files created in such a folder:

main.blpThis is the "BluePrint" format file for defining your interface. The BluePrint format is really compact, and this is the main way in which you type up your interface. Create widgets and give them properties (and data, if applicable); Workbench will check whether the syntax and writing are correct.main.uiA direct translation of everything inmain.blp(given that your syntax is correct), to an xml format that can be interpreted by the gtk builder. This file will be used by your program.settingsandjsconfig.json, two additional files used by Workbench.

When using Workbench, check its library for examples. These examples give you an idea of what is possible, and how to implement many common interface elements. You can ask for a live preview of your interface, and see how it works.

Showing an interface

To show one of these interfaces, created with Workbench or some other tool (Cambalache), you can use the GtkGladeWindow class provided by DUECA. In your module, add a member of this class:

When it is time to open the interface, usually in the complete method, give it the location of the .ui file:

Of course, now you have the window, but what can you do with it? For that, read the next section.

Simple button linking

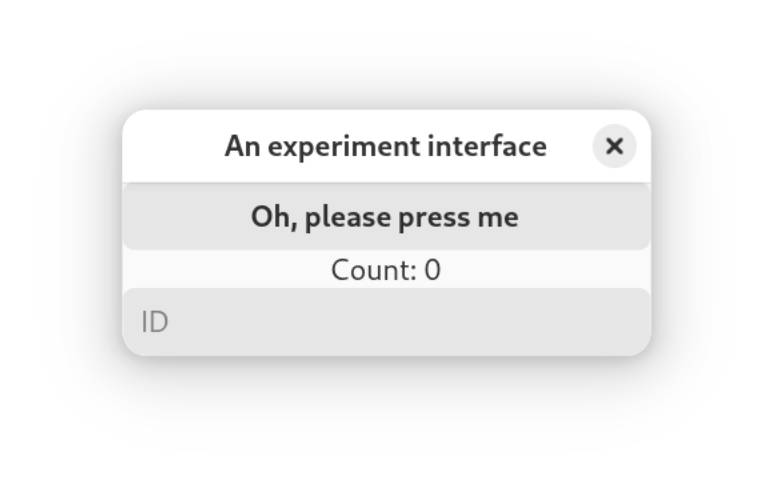

The widgets that you use in your interface all have their own possibilities to react to user input. Look at the GTK4 Documentation for the details. Most widgets have "signals" that can be emitted by the widget, and these can be used to trigger actions in your code (DUECA module). For example a normal button, can produce a "clicked" signal. Suppose that the mainwindow in the previous example has a button, and its BluePrint code looks like the following:

The window will have an id mainwindow, which will be important in telling GtkGladeWindow which widget to create as main widget, and the button has been labeled my_button. With the label, it will be accessible from the code.

To make sure that the "clicked" signal from the my_button arrives at our code, we need to link it to a function of the ExperimentInterface module. In your header, add this function; to see what it should look like, check the documentation for the "clicked" signal:

Instead of opening the window without further ado, we will use a callback table to tell GtkGladeWindow how the signal from the button is to be linked to the code, so re-write the complete function as:

Note that in the call to readGladeFile, now the this pointer for the module, and the callback table are passed. With this data, the readGladeFile function will connect all signals specified in the table to the newly created widgets in the interface. Whenever the button is now clicked, the cbMyButton function will be called.

Initialize the counter to zero in the constructor of your ExperimentInterface module. As an example for the button callback function, we could make this:

We can see a number of things here. First, I used the code in the handy boost/format.hpp to write a new label. The eciwindow object has a handy indexing function to look up widgets in the interface, we use that to get the label widget. This returns a GtkWidget object, the GTK_LABEL macro will convert/cast that one to a GtkLabel, which can then be used to change the label text. The c-style interface for the gtk widget toolkit might be a bit cumbersome, but it is precise and does a lot of checking, and personally I prefer this to using the c++ interface for it.

Sucking the data in to fill a DCO object

Of course, reacting to single button presses is not the only way to get data from the interface into your program. In most cases when making an interface like this, you want to collect the input on the interface (participant number, experiment condition to be used, options, etc.) into a DCO object that you can send around as an experiment or simulation configuration event. There are some handy functions built into the GtkGladeWindow object to help you there. Let's assume we have the following minimalistic DCO object:

Also assume you have defined an event write token w_expcond (left as exercise for the reader). We can now use the last element in the display, the text entry box, to show how data can be obtained from the interface and collected in a DCO object. Modify the button callback to:

Some explanation on how this works might be in order. The the eciwindow's getValues call is templated, and as argument it can accept DCO types created with DUECA's code generator. This call inspects both the DCO object and the interface, and then tries to fill all "matching" members of the DCO object, in this case an ExpCondition.

The "eci_%s" string specifies the format for looking for widgets. It will be combined with the name of the members in the DCO object (in this case the single member of the ExpCondition), here resulting in "eci_participantid". That is the name of the GtkEntry widget, so that will be matched, and the text found in the GtkEntry widget will be written in the ExpCondition object that will be sent off over the channel linked to w_expcond. By using a prefix (in this case "eci_"), we can avoid confusion with names of other widgets, and it will also be possible to extract multiple identical DCO object from the interface, as long as different prefixes are used in naming the widgets.

It is also possible to work the other way, with a setValues call, and set values from a DCO object in the interface. For a short overview of what types of data can be matched to what types of widgets, see the table below:

| data type | widgets |

|---|---|

| std::string | GtkEntry, GtkDropDown |

| double | GtkEntry, GtkSpinButton, GtkDropDown (with numbers), GtkRange |

| float | GtkEntry, GtkSpinButton, GtkDropDown (with numbers), GtkRange |

| int8_t..int64_t | GtkEntry, GtkSpinButton, GtkDropDown (with numbers), GtkRange |

| uint8_t..uint64_t | GtkEntry, GtkSpinButton, GtkDropDown (with numbers), GtkRange |

| enum | GtkDropDown (with enum values), GtkCheckButton (as radiobutton) |

| bool | GtkCheckButton, GtkToggleButton |

The GtkDropDown widgets can be loaded with values with the loadDropDownText call, for example to load a dropdown box with names of experimental conditions. The fillOptions call can be used to fill dropdowns with all possible enum values.

Linking an enum to a group of radio buttons needs some special preparation. In gtk4, radio buttons are created as GtkCheckButton widgets, which are then connected by setting the "group" property of all but one of these checkboxes to the id of the main checkbutton. To link these with the enum values, you need to specify these in the widget id; like so:

This would assume an prefix of eci_, then an enum in the option member of your DCO which can have values Default, HiGain and EasyDoesIt. Depending on which of these radio buttons is the currently active one, the enum value will be set.

Loose ends, getting or settina a single value

You do not always have to use a DCO object to get data from the interface, although in many cases it is by far the most efficient options. For loose ends, such as single floating point or integer values, or simple strings, you can use the (templated) dueca::GtkGladeWindow::setValue and dueca::GtkGladeWindow::getValue call. Given the eciwindow as used above, you could for example do:

Making a menu

In gtk4, menus are shown by specific widgets, such as the MenuButton, or attached to the whole application. The items in menus must be linked to actions to be enabled.

With Workbench, you can add a PopoverMenuBar or a MenuButton to your interface, which you can link to a menu that you define

Normal menu item

Within your program, you need to create the actions ("app.newfile", etc.) and connect them to a callback. Menu items that are connected produce the activate signal. We can re-use a gtk callback table structure, and do something like:

Toggle/checkbox type

If you want to use checkbox or radio selection functionality, your actions need to have a boolean state, using the g_simple_action_new_stateful call, for example:

Radiobutton type menu items

For radiobutton menu items, you need a stateful action with a string (or maybe integer also works?) value. In the action name, code the variant/selection of the radio button, as seen above in the "chooseoptions" actions.

List view

Tables with data are often useful for showing experiment results, or grouping a large number of similar options/data together. When the table size is not known beforehand (i.e., a variable number of rows will be produced), you can use the GtkColumnView to present this data. This is one of the big changes compared to gtk3, and although the resulting solution at first look seems more complicated, after having converted a number of these I can say that the gtk4 version is more robust, flexible, and it can be approached in a simple, step-wise manner.

Creating your data type

If you want to use a table with multiple columns in gtk4, you should define a data type to be used in that table. That data type needs to interact with the gtk4 system. In all likelihood you have already collected/joined your data in C++ classes (if you use OO design). It is best to make the datatype you create a thin shell to connect to your existing data. For argument's sake, lets suppose you created a DCO object with some stuff:

And as data comes in, you store these in a list, using a std::shared_ptr:

You need a datatype that is as "thin" as possible, compatible with the gtk (actually g) object system. Let's make the following, typically in your .cxx file, since you will use it only there:

For this example, let's assume that the score will be updated during the run (so its value in the table will change). To do that, we need to define the score as a property on the new datatype we are going to define. Create an enum for remembering that.

I hope most of this stuff is clear enough, and can be adjusted for your purpose. The "placement new" example is a safe way to initialize the data; for simple stuff (integers, floats, doubles etc.) it will not be needed.

Filling or binding?

The above give a new type that is a shallow link between your data and the gtk4 world. With this, we can define a piece of interface code with Workbench that should be able to show the data.

It has a number of typical components:

- The ColumnView, and we gave it a name, because we need to find it and link it to our data

- Three factories, which will create the widgets that are shown in the column view, and will link our data to these widgets.

The factories have two typical signals that need to be connected, "setup" and "bind". The ColumnView code is smart, in that it will create enough cells through the factories to fill the rows that are visible on the screen, and will fill these cells with the data from your application. To make that happen, you need to create a number of new functions for your class/module.

All three columns will be filled with label fields, and we can use the same setup function for those. However, the data connection differs, and we use three different bind functions.

In the complete() function, we need a new callback table. Look above for how to use it:

The label set-up function is simple, it creates a new label object, and gives it to the list item.

The bind functions should link the data in your application to the interface widgets. If the data does not change (like the participant id), you can simply copy the data over by setting the label string:

However, as an example, let's say we start an experiment, and the running score (for the same participant/run number) is regularly updated. To do that, you can create a dynamic binding, and that is why we created a "score" property on the new data type.

Now, in your doCalculation activity, you can check whether new data comes in for the score (assuming you created a channel for that), and if the run number changed, create a new entry in the list of results, or, if it did not change, update the score that you have. Here is some example code:

Tree view

TO BE COMPLETED.